The mighty cry of “All power to the Soviets”

SocialistWorker.org is continuing its series 1917: The View from the Streets with excerpts from a firsthand account of the revolution by socialist journalist , written for the New York Evening Post and published as a book in 1921. Along with the more famous Ten Days That Shook the World by fellow journalist John Reed, Williams' Through the Russian Revolution provides a riveting picture of the struggle to create a new society as Russian workers, soldiers, sailors and peasants began seizing control over every aspect of their daily lives.

In the excerpt below from chapter six, Williams describes the final days before the insurrection that toppled the Provisional Government on October 24-25 (November 6-7 on the calendar we use today) as the workers and peasants of Russia put their hopes in the workers' councils. SW's series on 1917 is edited by John Riddell and co-published at his website.

ANOTHER WINTER is bearing down upon hungry, heartsick Russia. The last October leaves are falling from the trees, and the last bit of confidence in the government is falling with them.

Everywhere recklessness--and orgies of speculation. Food trains are looted. Floods of paper money pour from the presses. In the newspapers endless columns of hold-ups, murders and suicides. Night life and gambling-halls run full blast with enormous stakes won and lost.

Reaction is open and arrogant. Kornilov, instead of being tried for high treason, is lauded as the Great Patriot by the bourgeoisie. But with them patriotism is tawdry talk and a sham. They pray for the Germans to come and cut off Petrograd, the Head of the Revolution.

Rodzianko, ex-President of the Duma, brazenly writes: "Let the Germans take the city. Tho they destroy the fleet they will throttle the Soviets." The big insurance companies announce one-third off in rates after the German occupation. "Winter always was Russia's best friend," say the bourgeoisie. "It may rid us of this cursed Revolution."

Despair Foments Rebellion

Winter, sweeping down out of the North, hailed by the privileged, brings terror to the suffering masses. As the mercury drops toward zero, the prices of food and fuel go soaring up. The bread ration grows shorter. The queues of shivering women standing all night in the icy streets grow longer. Lockouts and strikes add to the millions of workless. The rancor in the hearts of the masses flares out in bitter speeches like this from a Vyborg workingman:

"Patience, patience, they are always counseling us. But what have they done to make us patient? Has Kerensky given us more to eat than the Tsar? More words and promises--yes! But not more food. All night long we wait in the lines for shoes and bread and meat, while, like fools, we write 'Liberty' on our banners. The only liberty we have is the same old liberty to slave and starve."

It is a sorry showing after eight months of pleading and parading thru the streets. All they have got are lame feet, aching arms, and the privilege of starving and freezing in the presence of mocking red banners: "Land to the Peasants!" "Factories to the Workers!" "Peace to all the World!"

But no longer do they carry their red banners thru the streets. They are done with appealing and beseeching. In a mood born of despair and disillusion they are acting now--reckless, violent, iconoclastic, but--acting.

In the cities revolting employees are driving mill-owners out of their offices. Managers try to stop it, and are thrown into wheelbarrows and ridden out of the plant. Machinery is put out of gear, materials spoiled, industry brought to a standstill.

In the army soldiers are throwing down their guns and deserting the front in hundreds of thousands. Emissaries try to stop them with frantic appeals. They may as well appeal to a landslide. "If no decisive steps for peace are taken by November first," the soldiers say, "all the trenches will be emptied. The entire army will rush to the rear." In the fleet is open insubordination.

In the country, peasants are overrunning the estates. I ask Baron Nolde, "What is it that the peasants want on your estate?"

"My estate," he answers.

"How are they going to get it?"

"They've got it."

In some places these seizures are accompanied by wanton spoliation. The skies around Tambov are reddened with flames from the burning hayricks and manor houses. Landlords flee for their lives. The infuriated peasants laugh at the orators trying to quiet them. Troops sent down to suppress the outbursts go over to the side of the peasants.

Russia is plunging headlong towards the abyss.

Over this spectacle of misery and ruin presides a handful of talkers called the Provisional Government. It is almost a corpse, treated to hypodermic injections of threats and promises from the Allies. Before tasks calling for the strength of a giant it is weak as a baby. To all demands of the people it has just one reply, "Wait." First, it was "Wait till the end of the war." Now, "Wait till the Constituent Assembly."

But the people will wait no longer. Their last shred of faith in the government is gone. They have faith in themselves; faith that they alone can save Russia from going over the precipice to ruin and night; faith alone in the institutions of their own making. They look now to the new authority created out of their own midst. They look to the Soviets.

"Let the Soviets Be the Government"

Summer and fall have seen the steady growth of the Soviets. They have drawn to themselves the vital forces in each community. They have been schools for the training of the people, giving them confidence. The network of local Soviets has been wrought into a wide firmly built organization, a new structure which has risen within the shell of the old. As the old apparatus was going to pieces, the new one was taking over its functions. The Soviets in many ways were already acting as a government. It was necessary only to proclaim them the government. Then the Soviets would be in name what they were already in reality.

From the depths now lifted up a mighty cry: "All power to the Soviets." The demand of the capital in July became the demand of the country. Like wildfire it swept thru the land. Sailors on the Baltic Fleet flung it out to their comrades on the Black and White and Yellow seas, and from them it came echoing back. Farm and factory, barracks and battlefront joined in the cry, swelling louder, more insistent every hour.

Petrograd came thundering into the chorus on Sunday, November 4th, in sixty enormous mass meetings. Trotsky, having read the Reply of the Baltic Fleet to my Greetings, asked me to speak at the People's House.

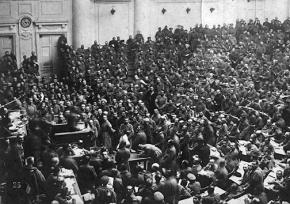

Here great waves of human beings dashed against the doors, swirled inside and sluiced along the corridors. They poured into the halls, filling them full, splashing hundreds up on the girders where they hung like garlands of foam. Out of the eddying throngs, a mighty voice rose and fell and broke like surf, thundering on the shore--hundreds of thousands of throats roaring "Down with the Provisional Government." "All Power to the Soviets." Hundreds of thousands of hands were raised in a pledge to fight and die for the Soviets.

The patience of the poor at an end; the pawns and cannon fodder in revolt! The dark masses, long inert, but roused at last, refusing longer to be browbeaten or hypnotized by the word juggling of statesmen, scorning their threats, laughing at their promises, take the initiative into their own hands, demanding of their "leaders" to move forward into revolution or resign. For the first time the slaves and the exploited, consciously choosing the time of their deliverance, vote for insurrection, investing themselves with the government of one-sixth of the world. A big venture for men unschooled in state affairs. Are they equal to these tasks? Can they control the currents now being loosed in the city? At any rate these masses show complete control of themselves. From these blood-stirring revolutionary meetings they pour forth in orderly fashion.

The poor frightened bourgeoisie are reassured. They see no houses looted, no shops wrecked, no white-collared gentry shot down in the streets. To their minds, therefore, all is well; there will be no insurrection. The true import of this restraint quite escapes them. The people indulge in no sporadic outbursts because they have better use for their energies. They have a Revolution to make, not a riot. And a Revolution requires order, plan, labor--much hard intensive labor.

The Masses Conducting Their Revolution

These insurgent masses go home to organize Committees, draw up lists, form Red Cross units, collect rifles. Hands lifted in a vote for Revolution now are holding guns.

They get ready for the forces of the Counter-Revolution now mobilizing against them. In Smolny sits the Military Revolutionary Committee from which these masses take orders. There is another committee, the Committee of a Hundred Thousand; that is, the masses themselves. There are no bystreets, no barracks, no buildings where this committee does not penetrate. It reaches into the councils of the Black Hundred, the Kerensky Government, the intelligentsia. With porters, waiters, cabmen, conductors, soldiers and sailors, it covers the city like a net. They see everything, hear everything, report everything to headquarters. Thus, forewarned, they can checkmate every move of the enemy. Every attempt to strangle or sidetrack the Revolution they paralyze at once.

Attempt is made to break the faith of the masses in their leaders by furious assault upon them. Kerensky cries from the tribunal "Lenin, the state criminal, inciting to pillage...and the most terrible massacres which will cover with eternal shame the name of free Russia." Immediately the masses reply by bringing Lenin out of hiding with a tremendous ovation and turning Smolny into an arsenal to guard him.

Attempt is made to drown the Revolution in blood and disorder. The Dark Forces keep calling the people to rise up and slaughter Jews and Socialist leaders. Forthwith the workmen placard the city with posters saying "Citizens! We call upon you to maintain complete quiet and self-possession. The cause of order is in strong hands. At the first instance of robbery and shooting, the criminals will be wiped off the face of the earth."

Attempts are made to isolate the different sections of the revolutionists. Telephones are cut off between Soviets and barracks; immediately communications are established by setting up telephonograph apparatus. The Yunkers turn the bridges, cutting off the working-class districts; the Kronstadt sailors close them again. The offices of the Communist papers are locked and sealed, cutting off the flow of news; the Red Guards break the seals and set the presses running again.

Attempt is made to suppress the Revolution by force of arms. Kerensky begins calling "dependable" troops into the city; that is, troops that may be depended upon to shoot down the rising workers. Among these are the Zenith Battery and the Cyclists' Battalion. Along the highroads, on which these units are advancing into the city, the Revolution posts its forces. They attack the enemy, not with guns but with ideas. They subject these troops to a withering fire of arguments and pleas. Result: these troops that are being rushed to the city to crush the Revolution enter instead to aid and abet it.

To these zealots of the Communist faith, all soldiers succumb, even the Cossacks. "Brother Cossacks!" reads the appeal to them, "You are being incited against us by grafters, parasites, landlords and by our own Cossack generals who wish to crush our Revolution. Comrade Cossacks! Do not fall in with this plan of Cain." And the Cossacks likewise line up under the banner of the Revolution.

Source: From chapter six of Albert Rhys Williams, Through the Russian Revolution. (Boni and Liveright, 1921), pages 89-97.

A note on Russian dates: The Julian calendar used by Russia in 1917 ran 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar that is in general use today.