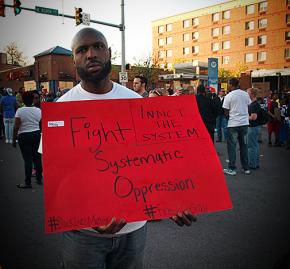

No sign of justice yet

With the prosecution of the cops who killed Freddie Gray dropped, looks at why the epidemic of police violence is continuing two years after the Ferguson revolt.

ALL OF the remaining charges against the Baltimore police officers responsible for the death of Freddie Gray in April 2015 were dropped after three of the cops were acquitted on all counts in the first trials held in recent months.

Gray's horrific murder--he was handcuffed and thrown in the back of a police van that was driven erratically so that Gray would be thrown around, causing his spine to be nearly severed--sparked a week-long uprising in the streets of Baltimore that the governor called in the National Guard to suppress.

Under intense pressure from the protests, Baltimore City State's Attorney Marilyn Mosby took the rare step of charging six officers with causing Gray's death. But after one mistrial and three acquittals, Mosby dropped all of the remaining charges--leading those who have marched and rallied against police violence in Baltimore and beyond to wonder: What will it take to hold the killer cops accountable for their crimes?

Mosby's decision came weeks after the murders of Philando Castile in Minnesota and Alton Sterling in Louisiana, captured on video, once again stirred huge protests. The demonstrations in over 80 U.S. cities represented probably the largest national wave of mobilizations since December 2014 when two grand juries refused to indict the officers who murdered Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York City.

Nearly two years after Brown's murder in Ferguson and the rebellion that followed, protests continue, sporadic but volatile--but so does the epidemic of police murder.

As if to highlight their continued impunity from any accountability, days after the charges were dropped, Baltimore police killed a 23-year-old woman and wounded her 5-year-old son after a several-hour-long standoff. Police are accused of deleting Korryn Gaines' social media accounts to hide videos she might have taken of them during the standoff.

AFTER TWO years, the bipartisan political establishment of this country not only has no answer to the epidemic of police violence--they won't admit it exists.

Instead, we hear political leaders bemoan the "crisis of trust" between police departments and Black and Brown communities or conflate the violence of police terror with "gun violence" more broadly in poor communities.

The outcome of the Freddie Gray indictments in Baltimore--which was an exception because there were indictments--is further evidence of the failure of the "justice" system to produce anything resembling justice.

This case should have been clear. The state medical examiner ruled Gray's death a homicide due to "acts of omission" by the police. So the state determined that Gray was murdered, but the prosecutor's decision to drop the charges is a statement that no one committed the crime.

This kind of logic would be farcical if it wasn't the common response when police kill. Officers are described as being "involved" in deaths, never responsible for them. Those who took a life avoid blame, though the victim is routinely slandered in the media and depicted as a criminal, even before their body grows cold.

And then we're told there's a "crisis of trust." What reason is there to trust the police, or any other part of the justice system?

In response to the protest movement that erupted after Ferguson and came to be known as Black Lives Matter, there have been meetings between political leaders and activists at the local and national level, a presidential task force, various Department of Justice investigations and firings of police chiefs and resignations of local officials. Yet the killings by police go on.

Not only have no police been sent to jail for their behavior, but activists are more likely to be arrested and incarcerated than the cops. In Pasadena, California activist Jasmine Abdullah was given a jail sentence for trying to stop a fellow demonstrator from being arrested--the charge against Abdullah more accurately describes what the cops themselves do: lynching.

A teenager in Baltimore was given a jail sentence for breaking the window of a police cruiser during the protests after Freddie Gray's death--while the police who killed Gray went completely free, as we know now. In Chicago, prominent activist Ja'Mal Green is facing five felony counts on trumped-up charges related to a protest earlier this month.

THE LATEST police murders captured on video--of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling--underline a fact that goes against all the rhetoric about the tough job that police have.

These killings, like so many before them, can't possibly be seen as police making mistakes in a difficult and threatening situation. Alton Sterling was selling CDs, and Philando Castile was pulled over for a traffic stop. Likewise, Freddie Gray "made eye contact" with a cop--that was all that was needed for a death sentence.

Sandra Bland also was driving, Eric Garner was selling cigarettes, Tamir Rice and Rekia Boyd were hanging out in parks, Michael Brown was walking in the street, and Trayvon Martin--killed by a self-appointed vigilante--was walking home from the convenience store.

These are not examples of conflicts that police had to intervene in. There was no wrong to a member of the community that had to be righted. Virtually all these killings were the result of racially profiled routine stops, suspicion of drug possession or distribution, and so-called "quality-of-life" offenses.

We don't need alternative methods for the cops to use in these circumstances. We just need them to stop.

Likewise, we don't need dialogue between poor communities and police departments, as if the problem were a lack of communication between victims and perpetrators. The problem is simply police killing people indiscriminately.

One example of how the "crisis of trust" approach derails a clear understanding of police violence is the recent statements of New York Knicks basketball star Carmelo Anthony.

Anthony is known for having spoken out in defense of Black Lives Matter and marched in Baltimore after Freddie Gray's murder.

After the killings of Castile and Sterling, followed by the mass shooting of Dallas police officers a few days later, he released an Instagram post that referenced Martin Luther King, Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali, and called on fellow athletes to "take action" and "demand change."

But his statement, alongside three other NBA stars, at the ESPY athletic awards ceremony was more ambiguous about the source of violence and what to do about it. He has also taken part in organizing a community forum with police officials and youth--with the stated aim of sharing perspectives and building trust.

Then there's Michael Jordan, the legendary star who has long rejected taking political stands. Jordan likewise made a statement against "the deaths of African Americans at the hands of law enforcement, but also against "the cowardly and hateful targeting and killing of police officers." He also donated to the Institute for Community-Police Relations, a group organized by the International Association of Chiefs of Police--not exactly a bastion of advocacy for victims of police violence.

AT THE same time, there has been an attempt to conflate police violence specifically with "gun violence" generally.

This was a strategy at the Democratic National Convention in July, when a group known as the Mothers of the Movement who have lost family members to violence--both at the hands of the police, self-appointed vigilantes and gang-related--took the stage.

Their suffering is palpable and moving. But it has to be said that the Democratic Party used their grief to push its agenda.

With chants of "Black Lives Matter" echoing through the convention hall, the mothers of Sandra Bland, Jordan Davis and Trayvon Martin expressed their support for Hillary Clinton, stating that Clinton's compassion and willingness to "say the names" drove their support, as well as her "commonsense gun legislation."

Obviously, gun violence is a major issue in many poor communities, but conflating that with police murder only serves to obscure the necessity of holding the police accountable--particularly considering that the typical solution presented to prevent violence is more police.

The Mothers of the Movement episode during the Democratic convention sought to portray Hillary Clinton as a defender of Black lives, but it was notable that the word "police"--the culprits behind the murders that sparked the Black Lives Matter movement--was absent.

But police chiefs sure weren't. They were featured speakers throughout the Democratic convention, including shortly before the Mothers of the Movement spoke, when Pittsburgh Chief Cameron McLay decried the recent shootings of officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge as "assassinations" while calling killings committed by cops "controversial officer-involved shootings."

After hundreds- and thousands-strong protests occurring, despite ebbs and flows, for two years, all we get from the Democratic Party--I won't even mention the Republicans--is talk about "communication" and "trust" without justice.

The protests to make Black lives matter have been inspiring and resilient. But they are not enough by themselves. We need a movement that draws in even wider numbers of people who are outraged by this injustice.

In Selma, Alabama, in 1965, 25,000 people marched to demand voting rights. The goal of limiting the monopoly of violence used by the state in the form of police is far more difficult one to attain.

Thousands of people have led the way in the early waves of the movement for Black lives. We now need to organize so that movement numbers in the tens of thousands and beyond.