“I speak for those who fell”

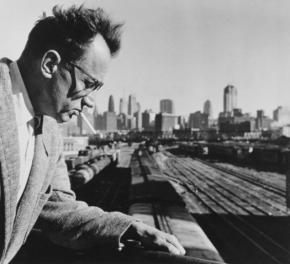

On what would have been his 100th birthday, celebrates Nelson Algren's stories from Chicago's forgotten citizens.

THE CHICAGO neighborhood that writer Nelson Algren wrote about in his novels and essays may seem a world away today. Upscale condominiums and eateries have replaced the rundown tenements and bars.

But in many ways, Algren--who was born 100 years ago at the end of March--would still find a lot familiar about Chicago, his City on the Make. It's a city where the mayor would sell City Hall if it weren't attached to the ground (though he has managed to sell a bridge or two, even in that condition), in a state where the last governor tried to sell off a Senate seat.

Algren would easily recognize the city's still-brutal and corrupt police. He would also see the same hypocrisy of so much wealth sitting beside so much poverty, from the Gold Coast to the West Side.

Frankie in Algren's The Man with the Golden Arm sees it this way:

The great, secret and special American guilt of owning nothing, nothing at all, in the one land where ownership and virtue are one. Guilt that lay crouched behind every billboard which gave each man his commandments; for each man here had failed the billboards all down the line. No Ford in this one's future nor ever any place all his own. Had failed before the radio commercials, by the streetcar plugs and by the standards of every self-respecting magazine. With his own eyes he had seen the truer Americans mount the broad stone stairways to success surely and swiftly and unaided by others; he was always the one left alone, it seemed at last, without enough sense of honor to climb off a West Madison Keep-Our-City-Clean box and not enough ambition to raise his eyes back to the billboards.

City "leaders" hardly appreciated Algren's rough and honest depictions of the people who ordinarily exist hidden from view in Chicago's poor neighborhoods in books and short stories like The Neon Wilderness, Never Come Morning and The Man with the Golden Arm.

After they saw Never Came Morning--which takes place in the Triangle neighborhood near Division Street and Milwaukee Avenue--the more "respectable" leaders in the Polish community tried to have the book banned because of its unwholesome Polish characters. They accused Algren of being in league with Nazis. The book was removed from the Chicago Public Library.

Years after his death in 1981, Chicago changed West Evergreen Street to West Algren Street, but residents complained that it was confusing, and they changed it back again.

When he was alive, he rarely made much money from his writing. He often complained how he never got his due--not from Hollywood, which butchered his novels, and certainly not from Chicago, whose civic leaders were likely embarrassed by his less-than-glowing portrayal of the "city that works."

BORN NELSON Algren Abraham in Detroit in 1909, Algren moved four years later to Chicago with his family. They were Jewish; his father worked as a mechanic. After he graduated from the University of Illinois, he bummed around the country, including Texas, where he was arrested and thrown in jail for stealing a typewriter. He took his Swedish grandfather's name Algren and started writing.

In the 1930s, Algren began spending his time in the bars and streets of Chicago's West Side immigrant neighborhoods, going to boxing matches, gambling tables and the line-ups at local police precincts--all the while gathering stories.

Algren could not help but be radicalized by the times. In 1933, the World's Fair opened in Chicago under the banner "A Century of Progress"--with a big sign over the front gate that read "No Help Wanted," as Hoovervilles sprang up on the outskirts of the fairgrounds.

During the Great Depression, the Communist Party (CP) helped set up John Reed Clubs around the country to gather together left-wing writers. Algren took part in one in Chicago, where he met Native Son author Richard Wright. He wrote for the fiction magazine, The Anvil. And while he never joined the CP, Algren supported their campaigns, like the anti-fascist fight in Spain.

A friend got him work in 1936 through the Works Project Administration (WPA) in the Federal Writers' Project. "It gave new life to people who had thought their lives were over," Algren said of the WPA. "It served to humanize people who...had...lost their self-respect by being out of work and then living by themselves began to feel the world was against them."

During the anti-Communist witch-hunts of the late 1940s and 1950s, Algren defended freedom of speech. He helped lead the Chicago Committee for the Hollywood Ten, writers and directors who had been blacklisted and jailed for being Communists, and was chair of the Chicago Committee to Secure Justice in the Rosenberg Case, who had been accused of "stealing the atomic secret."

In the 1960s, when the University of Iowa sent him on a lecture tour, Algren used the opportunity to speak out against the Vietnam War. In 1974, he moved to Paterson, N.J., so that he could write about the case of Rubin "Hurricane" Carter, the Black prizefighter who faced execution.

But Chicago was always the main focus of his attention--and it inspired his best writing. ''I'm stuck here," he wrote to his longtime lover, the French writer and feminist Simone de Beauvoir "...because my job is to write about this city, and I can only do it here...Without consciously wanting to, I've chosen for myself the life best suited to the sort of writing I'm able to do.''

ALGREN WAS able to write with the voices of the forgotten, the people living on the fringes of society, in a time when no one wanted to hear those voices. In an unpublished manuscript reprinted by Bettina Drew in her biography, A Life on the Wild Side, Algren wrote:

Being a loser I speak only for losers...

Being a loser I speak only for those who leapt or fell, losers being the only ones left with something to say and no one to say it.

All the time, day in and day out, in a city where everyone has to win every round just to stay alive.

Some fans of Algren may romanticize the down-and-out lives he depicted--the addicts, prostitutes and small-time criminals--as the "salt of the earth." But they would be as wrong as the civic leaders who would have preferred that Algren shut up.

Algren never romanticized the people he wrote about. He wrote with an honesty and understanding that people are more complicated than they are usually portrayed. No one is simply bad or good. Despite that, though, he shows us there is an "us" and a "them."

These themes are clearer when you compare Hollywood's depiction of Frankie Machine from The Man with the Golden Arm versus Algren's book.

This isn't to say that Frank Sinatra's performance isn't great to watch, but the movie simply misses what the book is about. Hollywood gave us an exposé of the life of a morphine addict, mysterious and soulful and sad and fated. But in the book, Frankie is more complicated--he develops his habit in the military--and so is the story, which has a lot to say about poverty, police brutality, prison and desperation. In fact, Algren said in a 1955 interview with the Paris Review that the addict component of the story was added in a later draft after a discussion with his agent.

While his portrayal of poverty is grim, Algren also manages to find the funny side, like a police interrogation in The Neon Wilderness, where a slippery sidewalk causes one guy to accidentally fall and break a jewelry store window, or so he says.

While Algren shows Chicago and its characters with all their terrible lumps and scars, he also has a sentimental side. It's clear that he cares for the characters that he writes about. In Neon Wilderness, he manages to take on the voices of an African American soldier from Memphis gone AWOL in Paris, and a woman who gets sent prison.

Algren not only understood the conditions of poverty in Chicago, but also its history of bloody class battles. As he writes in City on the Make:

Town of the hard and bitter strikes and the trigger-happy cops...

Where undried blood on the pavement and undried blood on the field yet remembers Haymarket and Memorial Day.

Most radical of all American cities: Gene Debs' town. Big Bill Haywood's town, the One-Big-Union town.

Those fights aren't over. As Algren wrote in his 1961 Afterword to City on the Make:

For the essay made the assumption that, in times when the levers of power are held by those who have lost the will to act honestly, it is those who have been excluded from the privileges of our society, and left only its horrors, who forge new levers by which to return honesty to us.