Putting their “bodies on the gears”

Fifty years ago this week, the Free Speech Movement at the University of California Berkeley reached its high point with a mass campus protest followed by an occupation of the administration building. When police moved in against protesters, the call for a student strike went out, and the campus was shut down in the coming days.

The Free Speech Movement was the spark that set off the campus revolts of the late 1960s, where activism against the Vietnam War was the most prominent issue. But the Berkeley struggle's roots lay in the civil rights movement. Here, and tell the history of the Free Speech Movement. SocialistWorker.org will continue marking this anniversary with an interview with Free Speech Movement participant Joel Geier.

NOW OFFICIALLY celebrated by the institution it fought against, the Free Speech Movement that shook the University of California (UC) Berkeley in 1964 wasn't about an abstract principle. It was a campaign led by radicals and revolutionaries who were determined to defeat segregation on the way to a more just and equal society.

Despite its liberal image, Berkeley in the 1960s was characterized by Jim Crow racism. Students at the UC campus were involved in civil rights organizing and community struggles, such as against discriminatory hiring practices. Between late 1963 and early 1964, dozens of students were among the hundreds arrested in protests against racist discrimination at businesses in the Bay Area. In July 1964, students also protested the Republican National Convention on the outskirts of San Francisco.

Thus, as veteran socialist and Free Speech Movement participant Joel Geier explained in an interview for SocialistWorker.org:

[A] minority of Berkeley's 25,000 students had already become engaged in political activity through the civil rights movement, and also in organizing opposition to Sen. Joseph McCarthy's anti-communist witch hunts...

This helped to instill a radical political culture on the campus, so that when the Free Speech Movement began in 1964, there were eight or nine radical political clubs on campus that defined themselves as socialist in some form or another. They had a membership between them of 200 to 300 people and a periphery of another 200 people.

Under pressure from the conservative business community, the UC Board of Regents--state-appointed governors of the UC system--pressured the Berkeley administration to take action against groups active in community politics. Student organizations were informed that they would no longer be allowed to use Sproul Plaza, at one of the main entrances to campus, to solicit support for "off-campus political and social action."

Activists realized this would deny them the best spot on campus to reach out to other students in order to build actions and raise funds. When student groups from across the political spectrum appealed the ruling, they were told that Dean of Students Katherine Towle didn't have the authority to do change the policy.

With this, students began to band together, writes movement participant Jo Freeman:

Calling themselves the United Front, the student groups defied the policy by setting up their tables as before, and also in front of the administration building facing Sproul Plaza, where they had never been before. Several students led a rally and march against the "new" regulations without getting prior permission--required by the old rules--to do so.

When five tablers were ordered to go to the Dean's office, some 400 students signed a petition of complicity and filled the halls of the administration building demanding that they, too, be disciplined. The deans announced that three names had been added to the "cited students" list, and all eight were "indefinitely suspended." At 3 a.m., the crowd left the building.

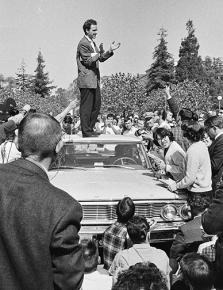

THE NEXT day, October 1, former graduate student Jack Weinberg was arrested while tabling for the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) in defiance of the ban. He was put inside a police car to be taken away for booking. But students spontaneously blocked the car.

Mario Savio--who had spent the previous summer teaching in a Freedom School in Mississippi as part of the civil rights movement's Freedom Summer project--mounted the police car and spoke to a growing crowd. He not only demanded Weinberg's release, but called for action in defense of students' right to free speech and protest. As Freeman wrote:

With Jack inside, the police car became the platform for a continual rally...Having no plan or strategy, the United Front made it up as they went along. Students once again occupied the administration building, clashing with police when they tried to close it early, but they left the building to spend the night around the car.

Near midnight, about 100 fraternity boys surrounded the few hundred students still there to heckle and pelt them with eggs and lighted cigarettes. They finally left after a Catholic priest pled for peace from the top of the car.

The United Front selected a negotiation group, but the campus administration refused to meet with them. Instead it arranged with several local police forces to arrest everyone who did not leave the plaza by 6 p.m. Several hundred police were brought on campus and lined up behind adjacent buildings. In the meantime, Governor Pat Brown ordered President Kerr to seek a peaceful solution with the protesters. Kerr invited them to meet with him at 5 p.m. in his office. After a contentious meeting, in which the students disagreed among themselves on what to do, the pact of October 2 was signed by Kerr and the United Front.

After more than 30 hours, Weinberg was released without charges. The cases of the eight suspended students were referred to the Academic Senate.

In the following days, the Free Speech Movement came together. It was the initiative of left-wing students, though even conservative student groups were encouraged to oppose the ban on campus politics. Radical students continued to organize and antagonize the administration, with graduate students forming their own organization as the struggle developed.

Freeman described the intensity of the organizing in the weeks after the October 1 confrontation:

An administrative apparatus grew up at Mario's apartment, soon called FSM Central, where meetings were planned, leaflets were drafted and phone calls made. Hundreds of students were energized by the conflict, and on their own produced numerous documents, an FSM button, and even a recording of FSM Christmas carols. Sales of the latter two items were the primary source of funds, plus donations.

Eventually, the Academic Senate recommended that six of the eight students who had been cited should be retroactively reinstated with only a censure on their records--but that Savio and another student, Art Goldberg, get six-week suspensions. This moved the fight to the UC Regents, who were due to meet on campus on November 20.

THE REGENTS laid down the law. Savio and Goldberg would get a semester of probation. Although the Regents supported a relaxation of the new speech rules to allow for some political activity that had been banned on campus, they upheld the idea of disciplining students who used the campus to pursue "unlawful" off-campus actions--meaning students who participated in civil disobedience actions off campus against racist employers or discriminatory housing practices.

A subsequent rally and sit-in at the Sproul Hall administration building did not win wide support. But the administration upped the ante with another threat of discipline against Savio, Goldberg and two other students.

That led to a call for another rally in Sproul Plaza--students were told to bring their sleeping bags. More than 2,000 people attended the demonstration. Savio delivered one of the most famous speeches of the 1960s era, when he implored fellow students to take action:

There's a time when the operations of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can't take part; you can't even passively take part. And you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you've got to indicate to the people who own it that unless you're free, the machines will be prevented from working at all.

After the rally, the occupation of Sproul Hall began, with more than 1,000 participants. Gov. Pat Brown--the father of current California Gov. Jerry Brown--ordered police to clear the building. Nearly 800 students were arrested.

As the arrests were taking place, the call for an immediate student strike went out. Despite the hasty preparations, it took hold and paralyzed the campus. In particular, graduate students played an important role in the strike's success--as Geier explained:

[T]heir organization had meetings every day of the strike to discuss how it was going, with reports from every department. In the social sciences and humanities, it was 90 percent effective, with 90 percent of the TAs out. The strike also spread to math and biology and physics--though it was a failure in places like business administration and engineering.

NEGOTIATIONS TOOK place during the weekend of December 5-6, and classes were cancelled for the following Monday, so the campus could attend an "extraordinary convocation" called for the Greek Theater. There, Kerr announced amnesty for all previous demonstrators--although those arrested would still have to deal with the courts--and tasked the Academic Senate with setting new protocols for political speech on campus.

But Kerr had allowed no discussion of his proposal. Mario Savio approached the microphone to try to announce a rally in Sproul Plaza to discuss what Kerr had put forward, only to be dragged offstage by campus police. The 16,000 students in attendance began chanting "Let him speak." Kerr eventually did, but this had destroyed the last illusions that there would be "free speech" under Kerr's proposal.

The faculty, which had been indecisive about Kerr's initiative, shifted to the side of the movement. The next day, the Academic Senate met and approved the Free Speech Movement's basic proposals for unrestricted political speech on campus. A conservative amendment was voted down 737 to 284.

The Free Speech Movement endorsed the decision and called off the strike. To seal the sense of an overwhelming victory, in the next day's Associated Student (ASUC) elections, five members of the pro-movement SLATE party were elected. The ASUC then endorsed the Academic Senate proposals on political speech and called for the Regents to do the same.

The Regents initially rejected the Academic Senate position at a December 18 meeting. In an attempt to regain their authority and initiative, they appointed their own committee to investigate. Two weeks later, however, they convened an emergency session and assigned liberal Free Speech Movement supporter Martin Meyerson to be the new chancellor of UC Berkeley. Meyerson granted the student demands and opened Sproul Plaza to free speech.

The free speech victory at Berkeley was just the beginning of the campus struggles to come. It paved the way for the development of the Vietnam Day Committee at Berkeley--a crucial formation in the later antiwar movement. As Geier explains:

After the Free Speech Movement, the left was no longer a small but significant minority at Berkeley. Its politics became the dominant politics of the whole generation.

And from there, the Free Speech Movement was the catalyst for the spread of radical student politics to campuses throughout the U.S. and internationally. For the next four or five years, the American student movement would be the largest and the most radical in the world--and Berkeley was at the center of it.