Could the union have won more at Con Ed?

reports on a deal that ends a key labor battle in New York City.

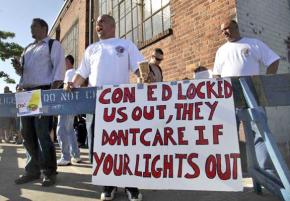

THE 8,500 members of Utility Workers Union of America Local 1-2 returned to work at New York City's Consolidated Edison after nearly four weeks of being locked out.

With a major storm approaching the tri-state area and fears of widespread blackouts growing, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo stepped in to pressure both sides to come to a rapid agreement. While the company's hope to gut the union through a prolonged lockout and its full wish list of concessions didn't come to pass, the executive board of Local 1-2 accepted more concessions than many members feel were necessary.

In particular, the union agreed to a two-tier pension plan, replacing the previous defined benefit plan with a "cash benefit" plan for new hires that doesn't guarantee a fixed income when they retire. The agreement also includes increases in health care costs for workers, and a portion of annual raises will be based on "merit." Plus, the company can fill up to 25 percent of job vacancies with outside contractors, accelerating the attrition of the closed shop.

For a company that made over $1 billion in every year of the previous contract, these concessions are unnecessary and send the message that workers can't expect the standard of living we had even five years ago, even while the bosses' wealth grows at a grotesque rate.

THE LOCKOUT began July 1. Local 1-2 offered to continue working under the old contract, but the company arrogantly and hypocritically claimed that its hand was forced by the union's refusal to agree to a seven-day notice for strike action. According to many members, the company fully expected the union to walk out as soon as the contract expired and reacted in frustration when it didn't.

However, the company clearly underestimated the members of Local 1-2 and the New York labor movement when they put 8,500 workers out on the picket line.

The first several days of the lockout were marked by confusion and passivity on many picket lines--managers who were replacing union workers were even greeted with hugs and smiles in some cases.

But it didn't take long for other locals--especially Communication Workers of America Local 1101, whose members at telecom giant Verizon are working without a contract themselves--to join the picket lines and bring a more militant energy. A "community solidarity meeting" of more than 50 union and social justice activists met to brainstorm ideas for a support campaign, including highlighting the racist dimension of power cuts, organizing for mobile picketing and touring locked-out workers to other unions.

When the company suspended members' health care benefits at the end of the second week, the union planned a press conference with bargaining unit members and dependents with chronic health conditions who had been cut off. The company suddenly "discovered" its error and reinstated coverage before the press conference could happen on July 15.

With a rally of several thousand union members and supporters from across New York's public and private sector on July 17, the tide began to turn. Shortly thereafter, Con Ed took out a full page ad in the New York Daily News offering to bring workers back if the union would agree to just a 72-hour warning period for a strike.

A handful of members began organizing mobile picketing--following scab trucks and visiting sites where contractors were moving heavy equipment or making deliveries--with sometimes dramatic results. Most union contractors respected Local 1-2 pickets and stopped work--a Facebook page became a focal point for posting scab work locations and reports on successful mobile pickets.

The energy and initiative from picket captains and rank-and-file members had just begun to solidify into meaningful organization when the agreement was reached.

One particular missed opportunity was the failure of the union to link the local's struggle to the racist character of where electricity cuts were being directed in the city. In a July 5 announcement, Con Ed published a list of neighborhoods that would suffer a 5 percent reduction in power--the vast majority were mostly non-white and lower-income areas.

Similarly, because of the history of racism in hiring, older workers tend to be whiter. The union has fought for more equal hiring practices, but now the company's demand for pension cuts for new hires will disproportionately hurt Black workers. One activist attending the solidarity meeting called this an "apartheid pension system"--that's a message many people in a predominantly people-of-color city could have related to.

THE UNION leadership's eagerness to accept a flawed contract despite the balance tipping in their favor exposes both their under-confidence--and how, for them, contract battles are more about the numbers than the culture of a fighting union.

Calculating the success of a contract campaign by looking only at the compensation package, and not at the relationship of workers to managers on the shop floor, reflects the mentality that views unions more as businesses than as vehicles for democracy and social justice. Unfortunately, this is the dominant strategy across the labor movement today.

Management at Con Ed is using a classic divide-and-conquer tactics by insisting on merit raises and the tiering of benefits. Union leaders use the logic that "we can't worry about those who aren't even here yet" in order to get those that are here to sell out future union members. The fact that these future workers will someday be in the position of defending--or not defending--benefits for retirees from the generation that sold them down the river is ignored.

Cuomo's participation is pressing for a settlement has received praise from the union and the press. However, some members are angry that a so-called "friend of labor" in the governor's mansion sat by while defined-benefit pensions were sacrificed on the alter of profit.

In an election year, major blackouts wouldn't have served Cuomo well, especially since many of donors to the Democratic Party live in wealthy Westchester County, where electrical lines are aerial and therefore more vulnerable to storms. Unfortunately, virtually no unions are willing to defy the Democrats--even if it means their own members suffer the consequences.

The logic for union leaders is that strikes and lockouts are difficult, dangerous things, so it's better to have them over with as soon as possible. Lost in the equation is the experience of being in struggle, which can transform people and build stronger organization for the fights to come. With the labor movement being hammered on all sides by employers and politicians, our side desperately needs some fights where we can use our power to disrupt production--and relearn some basic lessons of class struggle.

A handful of rank-and-filers who emerged as leaders during the lockout have begun to challenge the top-down approach in Local 1-2. They have already circulated a flier asking basic questions about the contract and the transparency of the voting process--while a summary is available online, members who want to see the actual text of the agreement have to read it at local headquarters. As the local appears to have no plans to clarify issues around the contract, members are petitioning for a special membership meeting. A "no" vote campaign may follow.

While the Con Ed contract is slightly better than many recent contracts--and much better than most coming after a lockout--it still falls short of what the company could afford and what members might have won after deepening their organizing. The struggle will continue.