The spring of the Egyptian revolution

The downfall of Hosni Mubarak was a historic achievement, but the revolutionary process in Egypt is ongoing. looks at the struggle for the future--this article was based on a speech given at the Left Forum in New York City on March 20.

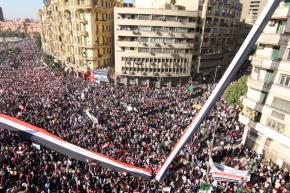

IT IS probably fair to say that the revolutionary uprising and process underway in Egypt is one of the greatest popular revolutions in modern history. The sheer numbers of those who participated in the uprising as well as their percentage compared to the total population is unprecedented and astonishing.

It is estimated that between January 25, when the demonstrations started, and February 11, when the dictator Hosni Mubarak was toppled, at least 15 million people out of a population of 80 million--that is more than 20 percent of the population--took part in the mass mobilizations.

A friend of mine in Cairo reminded me--and he was probably bragging a little bit--that 15 million protesters exceeds the total number of people who participated in all the protests that took place in all the countries of Eastern Europe at the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

It is true that young people led the charge on January 25, and that most of the 400 martyrs who were killed during the uprising were under the age of 30. But young people were not alone in the streets. From day one, the Egyptian uprising was a popular revolution. From day one, millions of workers, poor peasants, poor housewives and all sectors of society took part in the mobilizations across the country.

When you walked across Tahrir Square in Cairo, you saw group after group of poor workers of struggling government clerks; you saw peasants; you saw poor housewives who fight every day in order to keep their children fed and alive; you saw thousands of disabled people on crutches and wheelchairs, ignored by the government for decades; you saw thousands of retirees who can't afford meat and even certain kinds of vegetables; you saw men and women, Muslim and Christian.

All of these groups came to participate--and when the regime cracked down, they came to protect the youth who were leading the occupation of Tahrir Square.

The masses of poor and working-class people who took part in the uprising--as everyone else who took part--wanted democratic reforms. But workers and the poor also want social justice and the redistribution of the country's wealth after 30 years of privatization, impoverishment and neoliberal policies pushed by the Mubarak regime.

IT WAS truly a national uprising--every city and province up and down the country took part. Believe it or not, as militant and determined as the revolutionaries were in Cairo, which got most of the media coverage in the West, the revolutionaries in other cities such as Suez and Alexandria, the second largest city in the country, were even more militant and bolder.

For example, the protesters in Cairo concentrated on Tahrir Square and bravely held it for 18 days by fending off numerous bloody attacks by the police and Mubarak's thugs.

But in Alexandria, the protesters didn't adopt a Tahrir Square strategy. They didn't wait for the police to attack. The protesters came out every single day in the tens and hundreds of thousands from every neighborhood and street to confront the police--they fought back against police bullets and tear gas over and over again, until they defeated the police.

I listened online to an amazing tape of a radio communication between the police headquarters in Alexandria and commanders in the field, trying to deal with the flood of angry protesters. In the tape, police officers are begging headquarters for reinforcements to deal with what they described as massive and dangerous crowds of 10,000, 20,000 and 30,000 people, closing in on them everywhere in the city.

But the headquarters was helpless because all of the officers in the field--literally all of them--were asking for reinforcements. The headquarters advised officers and units to retreat to the precincts, and the officers responded: "Sir, protesters are burning the precincts."

The tape ends dramatically with the commander at headquarters asking a subordinate for an explanation for the police defeats. The officer simply told him: "Sir, it is over. The people are in the saddle."

The Alexandria story was repeated in Suez and city after city. Protesters marched on police precincts, on the headquarters of the Mubarak regime's ruling National Democratic Party (NDP), on municipal buildings, on governor's mansions, and on and on. And just as the revolt was massive, the celebrations that took place when Mubarak fell were breathtaking in their size and joy.

On the night that Mubarak resigned, 5 million of us celebrated in Tahrir Square for 24 hours. I thought it must have been the largest celebration in the country. I was corrected by friends in Alexandria, who told me: You have a population of 20 million in Cairo and 5 million came out. We have a population of 10 million in Alexandria and 7 million of us jammed the Mediterranean Boulevard, from one end of the city to the other.

I've read in books about great revolutions for social justice. I've read that millions who were involved in those revolutions not only change oppressive social institutions, but they also rediscover their humanity in the process.

I must say that I was lucky to have witnessed this process of social and human transformation firsthand in the few weeks of the uprising in Egypt.

I've seen and talked to so many people who tell you that they feel proud of what they did; they feel that they are no longer strangers in their own country; they feel human for the first time in their lives.

I have never seen so many millions in Egypt look more proud--so proud of what they and other revolutionaries accomplished, and so proud that they have done what they themselves never believed they could do.

People look more relaxed and at peace--you can see it on their faces. People in Egypt will tell you: Gone are the days when we felt helpless and little; gone are the days when the police could humiliate us and torture us; gone are the times when the rich and the businessmen think they could run the country as if it was their own private company.

Everywhere, people posted the January 25 revolution stickers--on their cars, in coffee shops, in their homes. Thousands of young people formed committees to clean up the streets in their neighborhoods. Thousands of others donated blood to those injured during the uprising. Young artists painted revolutionary graffiti, rejecting corruption and celebrating equality between Muslims and Christians.

In the days and weeks after February 11, one could sense the excitement and hope in the air. Indeed, the revolutionary uprising has brought big and amazing changes.

The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces--which took over from Mubarak in an attempt to save the social system from collapsing entirely, and which rules the country for the time being--made significant concessions to the revolution under intense popular pressure.

For example, the Council arrested some of Mubarak's corrupt political and business allies and froze their assets. It also froze Mubarak's own assets and promised to put him on trial.

On television in Egypt, you can see many hated figures from the business elite and from the regime, not smoking cigars in a fancy meeting, but wearing prison clothes and awaiting trial. You can see the despised former minister of the interior who ordered the shooting of protesters--not walking like an arrogant despot and spitting in our faces while his subordinates brutalize opposition figures, but wearing prison clothes and awaiting trial.

The arrest and trial of some high-profile corrupt officials were and still are a great source of euphoria for millions. But many ordinary people also realize that they made the revolution not just to punish a few figures in the old regime, but to change the whole regime.

Therefore, for many, Mubarak's ousting represents only the beginning of the revolution, not the end. Their slogan quickly became: In every corner of Egypt, in every factory, school and company, there are 1,000 smaller corrupt and criminal Mubaraks that we have to fight against and get rid of.

On February 12, only hours after Mubarak resigned, workers, students and even the oppressed Coptic minority all began organizing to end decades of exploitation and oppression. Millions of poor and oppressed people have been engaging in amazing and inspiring actions for social justice and democratization of all aspects of society.

But, of course, the Egyptian ruling class--which is wounded and shaken by the revolutionary upsurge--is still quite powerful and is fighting back to preserve its rule and privileges. It's doing so with the help of and under the leadership of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, which is a sanitized name for Mubarak's own top army generals.

In other words, immediately after Mubarak fell, an intense period of social and class struggle opened up in Egypt. Millions of workers and students began to try to shape the outcome of the revolutionary uprising through a series of daring and brave new round of struggles.

I WANT to give you a sense of some of these struggles, and I'll start with the unfolding workers' uprising.

There is no doubt that the strikes by industrial workers that took place starting on February 9 across Egypt were a key reason why Mubarak's generals decided that he had to go--before the revolutionary uprising could gain more depth and threaten the whole social system.

The council was definitely correct to be concerned. Since February 12, from within hours after Mubarak quit, workers all over the country--in the public and the private sectors--have been striking, protesting or sitting in. Oil workers, teachers, nurses, bus drivers, janitors, journalists and pharmacists--all the way to clerks in posh country clubs--have been organizing and protesting.

Workers' demands vary from one sector to another, but they revolve four main issues:

Workers everywhere want to raise wages and benefits; they want permanent status for the millions who have been working as temporary workers, sometimes on contracts as short as three months; they want an end to the neoliberal policies of privatization of companies, and many in the public sector are calling for the renationalization of companies that were privatized and sold to investors at below market values; and they want the ouster of all the corrupt CEOs appointed by Mubarak.

This last issue goes to the heart of the struggle for economic democracy. In the crucial industrial city of Mahalla, for example, 24,000 textile workers struck last month, drove out the corrupt CEO, and forced the army to accept their own nominee as the replacement.

It is the same story in other factories and companies across the country: workers' expectations are very high, and their militance and confidence is phenomenal.

Two weeks ago, near my house in central Cairo, I witnessed one of those militant strikes firsthand. Some 1,200 government print workers who produce school curriculum books went on strike to protest low salaries--an average of $100 a month--an outrageous CEO salary of $60,000 a month, disrespectful treatment at work, temp contracts, terrible health care provisions and on and on.

Three hundred workers attempted to rush the building to get to the CEOs office, but an army unit stopped them. So the strikers laid siege to the company building and locked their corrupt CEO in his office on the fifth floor for 36 hours.

The army officer in charge, along with a union representative, negotiated over the workers' demands with the CEO for 24 hours. The army officer forced the CEO to concede 90 percent of workers' demands so he could disperse them. The CEO caved in, and the army officer and the union rep came down and announced the settlement. The strikers were ecstatic and almost dispersed.

But some angry young workers whose temp contracts had been recently terminated were infuriated and attempted to storm the building again. Meanwhile, an older, militant woman pleaded with the rest of the workers not to abandon the youth. Most of the crowd decided to stay. They sent the union rep and the army officer back upstairs to tell the CEO to reinstate all temp workers, and offer them permanent contracts immediately. And they instructed the union rep not to come down again without a "yes" on all their demands.

This is an example of the kind of militant strikes, sit-ins and hunger strikes that are taking place all over the country every day in Egypt. Workers are also breaking with the government-run union federation and forming independent unions. A section of militant workers are in the process of forming a new political party: The Workers' Democratic Party.

I also want to briefly describe some of the student initiatives and struggles.

When the army finally opened schools and universities again after Mubarak's downfall, millions of students, teachers and professors--many of whom were part of the January 25 uprising--opened a new front of struggle.

In one university after another, mass student and faculty rallies are taking place to elect college presidents and deans in order to get rid of those appointed by Mubarak. In some universities, students are camping out--following the model of Tahrir Square--to win their demands. And in all of the colleges, the students forced the government to finally implement a year-old court order to remove secret police from all campuses.

High school and middle school students also formulated their demands and grievances. They rallied to demand an end to corporal punishment and removal of all sections in the curriculum that refer to Mubarak's so-called accomplishments. The ministry of education has complied.

But this is only one part of a wave of struggles for democratization that is sweeping every corner and sector of society. Journalists are ousting pro-Mubarak editors. Cinema actors and workers rebelled against the autocratic union president. Fans are boycotting many of their once beloved famous actors and singers who supported Mubarak. Soccer referees are threatening to strike over pay. Non-soccer athletes are demanding that sports clubs stop spending all their money on soccer players. The Boy Scouts of Egypt are demanding elections--and on and on.

Soccer fans go to soccer games in Egypt, but very few fans actually bother to watch and cheer for their team. Organized fan groups that took part in the revolution and lost martyrs are angry that their idols, the big time famous players, didn't show up in Tahrir, and that some of them openly supported Mubarak. The fans taunt those players at games with angry chants and with huge banners. One of these banners at a recent game read: "We supported you every second and everywhere, but where were you when we needed you?

When the uprising in Libya began, fans went to a game with a big banner in the colors of the Libyan, Tunisian and Egyptian flags--it read: The Free Republic of North Africa.

At every game, you find hundreds of people still chanting against Mubarak and the former interior minister, or calling for the removal of governors and so on.

OF COURSE, the emergence of these revolutionary forces across society has been met from day one with vicious opposition from the ruling class.

The Egyptian capitalist class is stronger and more established than the elite around Ben Ali in Tunisia or the Libyan regime of Muammar el-Qaddafi. Now, this ruling class is using all its ideological and sometimes repressive powers in an attempt to end--or at least slow down--the flood of struggle among workers and the poor.

Since February 12, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces has followed a policy of rejecting--or stalling on--every popular demand of the January 25 revolution in order to demoralize people.

For example, the Council initially rejected the popular demand to dismiss the last cabinet appointed by Mubarak. It also rejected the demand to dismantle the entire secret police apparatus and vowed only that it would be reformed. The Council daily denounces striking workers and calls on them to return to work. In some cases, it has tried to arrest strikers.

As well, remnants of the NDP and secret police burned a Coptic church in Helwan, south of Cairo--in order to whip up a civil war atmosphere between Muslims and Christians, with the hopes of splitting the revolutionary camp. Then, while the army stood watching, thugs organized by the NDP attacked Christians who were protesting the church burning in one poor Cairo neighborhood--they killed nine and injured dozens.

More recently, the army refused to draft a new constitutional declaration and insisted on forcing people to vote on nine amendments to the 1971 constitution written under the Mubarak dictatorship. Moreover, soldiers brutalized protesters at Tahrir Square on March 9, using electric batons and torturing those it arrested for hours in its field headquarters in the Egyptian Museum.

I have to be honest that for a few days toward the end of February and the first days of March, there was a widespread feeling of anxiety among millions of people who support the revolution that all was not going well--that the revolution was under siege at best, and counter revolutionary forces were actually winning at worst.

Fortunately, though, the deep reservoir of revolutionary aspirations and readiness to struggle to win our demands turned the situation.

First, mass demonstrations and an unrelenting popular opposition finally forced the Council to dismiss the Mubarak cabinet on March 3.

Then, on March 4, while millions were celebrating this victory, revolutionaries laid siege to the headquarters of the secret police in Alexandria and shut it down. The next day, protesters marched on secret police headquarters in city after city. In some places, protesters occupied these buildings, freed political prisoners in torture chambers and walked out with tons of secret documents, detailing repression and torture.

This courageous move by thousands of protesters forced the army to occupy and shut down the secret police headquarters in numerous places. A week later, as millions were still reading through the documents that were taken away from these buildings, the army finally dismantled that heinous institution and arrested dozens of its officers, charging them with corruption and torture.

The dismissal of the Mubarak-appointed cabinet and the defeat of the secret police gave a tremendous boost to everyone who supports the revolution.

That same week, mass mobilizations by Christians to protest the burning of the church in Helwan produced another important victory for the revolution. Tens of thousands of Christians, along with large numbers of Muslim supporters, occupied the north side of Tahrir Square, laying siege to the TV building for eight days to demand that the army rebuild the burned church and provide protection to Christians. After the eight days, the army caved in and rebuilt the Church.

This was not only a great victory for Christians, who have been systematically discriminated against for decades, but widespread solidarity from Muslims for the protesters at the TV building and elsewhere in the country reignited a sense of common destiny--defeating for now the counter-revolutionaries' divide-and-conquer schemes.

THE NEXT few days and weeks in Egypt are certain to lead to a continuation of the social and class polarization that erupted after February 11.

On the one hand, the Supreme Council and the new Cabinet have escalated their anti-revolutionary rhetoric and measures. They are supported by large sections of the frightened middle classes and, of course, the wealthy.

For example, the Cabinet recently announced a draconian law that would criminalize certain protests and strikes in periods of emergency in the future. The army also attempted to use force to break up a 10-day sit-in by students in the school of mass communications at Cairo University to demand the dismissal of a corrupt dean.

Both the army and the cabinet can now rely on a new ally in their campaign for "stability" and "law and order": The Muslim Brotherhood and the Islamic Fundamentalist Group.

The Muslim Brotherhood and the more reactionary fundamentalists campaigned in favor of passing the cosmetic constitutional changes proposed by the Supreme Council. These groups turned the referendum into a vote on the "Islamic" identity of the country. They told people that it was their religious duty to vote yes in order to prevent the establishment of a secular state with equal rights for the minority Christians.

Incredibly, in this effort, the Muslim Brotherhood formed a de facto bloc with their former jailors, Mubarak's NDP. The NDP is discredited, but has yet to be dismantled--and it was the only other political group in the country to support the army's proposals.

So the fundamentalists are attempting to polarize the country along religious line and weaken the unity between Muslims and Christians forged since January 25--something that can only benefit the old regime.

Meanwhile, remnants of the old secret police are attempting to wreak havoc in the country through an arson campaign directed at Interior Ministry buildings--in order to cover their past crimes--and through threats to assassinate public figures who support the revolution, such as Mohamed ElBaradei and Kefaya leader George Ishaq.

Nevertheless, during the middle of March, there were a number of positive developments on the side of those who support the revolution.

First, a growing minority of people who initially supported the Supreme Council and believed the lie that it aims to defend the revolution is rethinking its position. Sections of activists that were quiet before are now publicly criticizing the timidity of the Council in meeting the revolution's demands for democracy and social justice--something you could not do in the first few weeks after February 11. Some are drawing the conclusion that the army is complicit in counter-revolutionary actions.

Second, workers' strikes continue to spread and become more militant. For example, as of this meeting on March 19, thousands of television workers were carrying out a sit-in inside and outside the government-owned TV and radio building near Tahrir Square. They are demanding democratization of the institution, higher wages and the removal of all managers who supported Mubarak. They are threatening to take television off the air if their demands were not met.

Railway workers shut down all train movement in the south of the country, thus cutting off all entries and exits to the tourist cities of Luxor and Aswan, in an effort to push their demands for fair wages.

Meanwhile, workers continue to build new independent unions. On March 25, thousands of mass transit workers--whose strike during the uprising was instrumental in paralyzing Cairo and bringing down Mubarak--announced the formation of an independent union after a four-year struggle against the government-run federation.

The same day, hundreds of nurses, workers and doctors at Manshiat al-Bakri Hospital in Cairo announced the creation of a single united independent union after two months of feverish protests and organizing. Mahalla textile workers and many others have also formed new unions.

All these groups are joining the newly formed Egyptian Federation of Independent Trade Unions--and in mid-March, the pressure of strikes and protests forced the new cabinet to change the old labor laws and recognize all independent unions.

As the Muslim Brotherhood, Islamists and liberals all scramble form new political parties ahead of elections that will take place later this year, workers and the left are also initiating their own organizations and parties to fight for workers' demands and a radical democracy. For example, hundreds of militant trade unionists have come together to initiate the Workers Democratic Party. Also, hundreds of socialists, progressives and unionists are forming a broad left party called the Popular Coalition.

In universities, large groups of professors and teaching staff have been supporting and joining in on all kinds of student mobilizations to democratize the campuses.

On a neighborhood level, popular committees to defend the revolution, initiated by socialists and other activists in Tahrir, have spread to more than 11 governorates--the Egyptian equivalent of states. These committees of organized thousands for mobilizations around social justice issues and in favor of purging all remnants of the Mubarak regime.

In contrast to the Supreme Council and the cabinet, which ignored women in all their appointments to ministries and constitutional committees, women play a much bigger role in the new unions, left parties and the popular committees to defend the revolution.

MOST OF what the Egyptian revolution achieved in democratic changes after February 11 can only be attributed to massive popular pressure and courageous mobilizations of thousands of revolutionaries, such as the marches on the secret police headquarters.

Consciousness about the new situation is still developing. Millions of people who support the revolution have not yet joined in these activities. They are still waiting for the Supreme Council and the new cabinet to fulfill its promises of raising wages and eliminating all vestiges of corruption by the business elite.

However, the Council and its cabinet daily show their contempt for the masses of poor people--to the point where the new prime minister compared strikers to street thugs.

As time passes and the promises by those defending the old system are broken, the revolutionaries could win over millions of new recruits to their efforts. And as millions join the revolutionary wave across the Arab world, the balance of forces can continue to tip against the old order.

The current organizing efforts by workers, students and political activists are laying the basis both for much bigger rounds of struggle and for an alternative to the reactionary projects of the old ruling class and the fundamentalists. As one revolutionary likes to put it: "The spring of the Egyptian Revolution has just started."